Illuminations

It’s Not Always Pretty: Wabi Sabi, Shadows and Creative empowerment

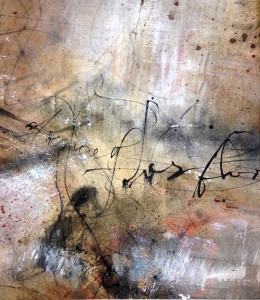

If the intention in our art is authenticity, then nothing gets spared or glossed over. Shadows are engaged and reckoned with as much as sunshine. What is ugly or repulsive to us may be compelling to others, worthy of as much attention, acceptance and praise as our more conventionally “lovely” creations. What scares us most may be our most resonant, emotionally powerful art. There are finished pieces from which I have recoiled in horror, like a mother who has birthed a monster, only to be shocked by the positive reception it receives when I reluctantly present it to the world. Why are we drawn to messy, layered visual journals with cracked, worn bindings, the bold primitive marks and scrafitti of a child’s drawing, the frayed golden dandelions peeking through sidewalk cracks, distressed, worm-eaten, antique wooden tables? Why do we take photos of an old rusted truck in a field covered with weeds and wildflowers, our grandmother’s gnarled, blue-veined wrinkled hands, or graffiti layered walls in urban alleys? Why was my own (self-rejected) wild, messy art piece—the first of its kind in my repertoire—appealing to its eager buyer? Wabi Sabi offers a clue. A Japanese term which defies clear definition, Wabi Sabi might best be understood as the beauty of transience, imperfection, simplicity. While Wabi Sabi defies definition, we recognize its organic qualities of rustic authenticity: wrinkled faces, distressed furniture, cracked walls with peeling paint. Wabi Sabi widens our aesthetic lens beyond a narrow, conventional Western ideal of beauty based on harmonious, classical proportions.

Prior to learning about Wabi Sabi, I loathed the muddy, quirky, disheveled intruders who kept showing up on my neat white pages and canvases. They arrived in tangled, layered slashes of energetic lines and marks, or brooding, primitive figures which thwarted my attempts to create neat,”well-behaved” lovely and “agreeable” calligraphic art pieces. Curious about what compelled me to express these visually (for me) challenging pieces and why people responded to them, I turned to C.G. Jung and his work on the Shadow.

According to Jung, We all possess a well-spring of unconscious, unknown or rejected aspects which comprise our personal shadow. These hidden parts not only have power and resonance, but can wreak havoc in our lives unless we bring them to light. Our acceptance and integration of our shadow is necessary for personal growth and wholeness. The personal art pieces which I had deemed ugly—which felt alien, shadowy unfamiliar—illuminated hidden aspects of myself, including a daring, assertive, disruptive feminist voice who could not be expressed in the language of conventional beauty. Embracing my “shadow” was catalyst for creative empowerment and a Wabi Sabi epiphany: Our “rough and tumble” rustic creations and our conventional, classically, harmonious “bright stars” can co-exist in equal measure of beauty, emotional resonance and impact. Regarding the not so pretty bits, I think of Lettering master Yves Leterme who suggests that to avoid preciousness in our art we may have to “kill our little darlings.” Conversely, I believe we are wise to accept some of the ugly ducklings or “Shreks” who arrive bidden or unbidden on pages and canvases. Perhaps like Shrek, who was filled with “rabid self-esteem” when he first saw his hideous visage in the mirror, we too can embrace the power of our shadow, welcoming what shows up in our work, warts and all.